Prospects for Peace and Justice?

An Israeli-Palestinian Dialogue

Introduction

On 12 November 2025, the University of Zurich, the University Research Priority Program (URPP) Equality of Opportunity, and the Zurich Program on Law and Normative Reflection (NORMZ) hosted the event “Prospects for Peace and Justice? An Israeli-Palestinian Dialogue” to discuss various dimensions and challenges surrounding the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Introductory remarks by Prof. Dr. Matthias Mahlmann

We all live in terrible times. There are many reasons for concern – politically, economically, ecologically – and the world is also ravaged by awful wars, in Sudan, Ukraine, and of course the region which is of our concern tonight. We all remember the atrocious attack on 7 October killing 1’200 persons and taking 251 hostages, many of whom died as well. We have also witnessed the Israeli campaign in Gaza, the horrible death toll of more than 70’000 people and other casualties and enormous human suffering.

So, you may ask the question: “Why do we discuss prospects for peace and justice? Isn’t that naïvely utopian given the hatred, the suffering, and the crimes committed in the last years?” We thought that many issues are important in this context, but also this issue deserves one evening of reflection. And there are at least three reasons for this: Our actions, our understanding, and our hopes.

As to actions, Switzerland is not a political party in this conflict, but of course we are also political agents from possible diplomatic actions, economic help, joining certain initiatives, up to our interactions and communications with Israelis and Palestinians about this issue. And it seems to me that we cannot take political action if we don’t have an idea what kind of future could be possible after what has happened. Without such an idea our political action lacks directions. Our choices depend on some kind of idea how the future could look like.

The issue is also important for our understanding. One of the strange properties of human beings is that they try to understand not only planetary motions but also their times, their epoch. And definitely the conflict that we are talking about is one of the pivotal elements of our current ongoing century. It is therefore, I think, important to ask whether there is some kind of way to break this cycle of hatred, suffering, and suppression, to somehow decipher the meaning of this event for our epoch.

And the third reason has to do with our hopes. The suffering is simply unbearable and there is an urgent imperative to try to find some kind of way ahead – obviously not with the hope to create some kind of paradise, but a way where people don’t die, where perhaps some kind of peace is achieved and perhaps even some kind of justice is achieved in this difficult conflict.

We are happy to have as speakers of this dialogue the distinguished public intellectuals:

- Amal Jamal, Professor of Political Science at Tel Aviv University

- Samer Sinijlawi, Political Activist and Writer in East Jerusalem

(from left to right: Amal Jamal, Samer Sinijlawi, Matthias Mahlmann. Image: Roger Stupf)

Both speakers were not invited as representatives of a specific political fraction, group, or identity. They were invited as thoughtful individuals who have something interesting and important to say about this conflict. We are trying to step out of some narrow-minded identitarian groupthink and trying to let the voice of individuals being heard again.

Dialogue

We recorded the dialogue and are making it available here with the consent of the speakers.

Note regarding the recording: Do not replicate or republish this recording without prior consent. Especially, do not extract or republish selective parts in order to hide, obscure, or alter the context of what has been said.

Quotes

Amal Jamal

Opening Statement

“[…] Between the river and the sea, as many people know, there are seven million Jews and seven million Palestinians – and none of them is going to evaporate, none of them is going to leave, none of them has a different home to go to. And I think we need an epistemic shift in order to first recognise that this reality of fourteen million people living there deserve to live in security, peace and justice and deserve to be given an open horizon for the next generations based on moral ethical principles of mutual respect and recognition. I think without this – and I’m starting from the end as you can see – without this nothing can happen.” (12:21)

“This tragic conflict occupies every piece of the land, of the psyche of the people living in the land, of their economy, of their daily life, of their dreams, of their wishes, desires, and so on. And I think we have to take that into consideration if we want really to deal with what’s going on, if we want genuinely to leave cliches and to leave slogans aside and deal with the reality.” (13:48)

“The consequences of what happened in the last couple of years are so deeply engraved in the psyche of all people on the ground, that it’s really difficult to speak today of a shift, of making a difference, of prospects of peace – people are so injured on the ground having lost many dear people around them.” (15:41)

“The lesson I would like to put here is that, as a result of this tragic reality, nobody, including the two sides, can sideline the two sides. […] There is one lesson at least to learn here: Sidelining one of the sides is not a bright path. And I would like to say it bluntly here: We have to communicate. Communicating with each other is a basic thing, it’s a human issue. And because of the differences, because of the pain, because of the tragic reality on the ground, there is a need for communication – boycotting one of the sides is not the right path in my view.” (16:40)

“The solution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a complex issue. It touches every piece of our being.” (24:37)

“If we want really to create a shift, a change, we don’t have to start with what the solution is. I think we have to start with defining the principles based on which we would like the solution to take place.” (25:12)

“Language is not neutral, it’s political. And I think we have to change the discourse, we have to create this epistemic shift in order to see differently what’s going on and introduce a different language – […] a language of the principles based on which people can live together.” (25:50)

“For a moment at least, we have to allow ourselves the right to be able to think, neutrally as much as possible, about based on what values, based on what hopes, based on what principles we would like to run our life. And if we ask this question, I assure you that most Israelis and more Palestinians will agree.” (26:40)

“A different reality has to be imagined and realised by the people there – all people there.” (33:00)

Dialogue

“One of the basic things I learned through the years is that these two people know each other very well. They really know each other very well. And they suspect each other very well. And they distrust each other very deeply. And human psyche in times of threat is very hard to change.” (01:04:00)

“The only people that is able to legitimise Israel […] is the Palestinians. The only people in the region that could relax the Israeli psyche is the Palestinians. This is a great responsibility.” (01:07:34)

“A central argument made by Jacques Derrida, the French philosopher, regarding forgiveness is “forgiveness has a meaning only when you forgive the unforgivable”. And forgiving the unforgivable is a matter of maturity and it’s not easy to achieve. That’s why I think we have to take this conflict seriously. It’s not naïve. It’s serious. It’s deep. It’s deeply engraved in the psyches of people and therefore it’s a huge amount of work. […] We have to take people more seriously and try to give them more sense of security.” (01:08:09)

“The Palestinians have never been given the chance to be free hosts historically. […] There are deep roots of ethical thinking in the Israeli-Jewish society. And the examination is to rise up to this place to have mercy, empathy and a place for the refugees. And the Palestinians are the refugees today. The Jews were the refugees of human history for hundreds of years, now the Palestinians are in this place. And I think the Jews are under examination. […] I’m part of this society, I’m part of the responsibility, and it’s my role to say this to every person: We have to rise up to a place where we can be the hosts of refugees, of weak people. And that’s how peoples historically are examined.” (01:13:35)

“Between the river and the sea there is a lot of pain, a lot of anxiety and fear. I’m not a psychologist myself, but I think political psychology is very present and we have to address that by opening new channels of communication. […] This is important for any conflict, definitely for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, not because people don’t understand each other, but actually because people know each other and suspect each other to want to do them harm. And I think this is difficult to change, but it’s the main mission we have to take responsibility for […]. The more we have communication, the more I think we are able to shift people’s minds and hearts in order to vote in the right direction and accept the other as a legitimate partner for common change.” (01:44:05)

Samer Sinijlawi

Opening Statement

“The diversity of Jerusalem creates some kind of unique identity. I used to start my mornings in my school, collège des frères la salle school, doing the Christian prayer, because that is the norm in the school, and I used to go in the afternoon to home and my grandfather takes me to the Al-Aqsa Mosque for the Muslim prayers. And I was fine with both. In Jerusalem sometimes you feel seeing people going to churches or mosques or even synagogues is part of your identity. Talking so many different languages is part of your identity. Until the first intifada came in 1987. I was almost fourteen and a half years old. Suddenly, I started realising there is “us” and “them”. They are in the uniform […] and we are in Keffiyehs. You see it in television. And somehow it invades you. It invaded me from inside. The first intifada gave me a new identity: The identity of the conflict.” (36:23)

“It was not the family, it was not the education system, it was what’s happening every day, every hour in our environment, that makes a kid like me start throwing stones, and maybe Molotov cocktails, that led me to lose my classmate, he’s the first Christian Palestinian that lost his life during the first intifada, in my hands, in the streets, shot by an Israeli soldier. And then this got me into five years in prison, in Israeli jail, from the age of fifteen to age twenty.” (37:54)

“And one of the hardest memory I have from that experience was first after 37 days of interrogation in what’s called section 20 – it’s the section in the Russian compound, Russian compound in Jerusalem is some kind of interrogation centre, one section of that interrogation centre is not part of the police investigation, it’s part of the Israeli intelligence, the Shabak – so I stayed 37 days there in the interrogation; when I went out for a court session, I saw my family for the first time after 37 days, it took me like three minutes to recognise them, because the psychological intensity of the interrogation is not something easy.” (38:35)

“Yet, I’ll tell you that this experience of jail is one of the best experiences in my life because it taught me a couple of things. First, I started to be more independent. […] Second, it taught me to be patient – you cannot rush time in prison, not with a Swiss watch. Time is time, you need to be patient – count days and be patient. Third, I learned my Hebrew.” (39:33)

“But this time also opened my eyes on the other side. The other side was the guards, both of us spent a lot of time behind bars. And we talk: We talk stories, we talk names, we talk family members. Somehow the guards were our window to the outside world. And I started my dialogue with the other side from within jail.” (40:22)

“Nobody can understand any conflict if he cannot see the conflict from the eyes of both sides.” (41:53)

“In spite of our obligation to deal with the main challenge for Palestinians which is the Israeli occupation, we also have the obligation to deal with internal issues. Palestinians deserve democracy, they deserve reform.” (46:42)

“[…] We need to find a way of how, despite of everything that is running against us, we need to find a way that we can push things, that we can be positively involved.” (47:57)

“I think it’s [the conflict] taking place because of mainly confusion. There is a lot of confusion on both sides. You spoke about change, I agree with you: There should be some change dramatically. And I think it starts in us trying to investigate our narrative. Do I really need, as a Palestinian, to deny the historical links of Jews in the land in order to prove my historical links to this land? Not necessary. Do Israelis and Jews need to continue claiming exclusivity of rights in the land to justify their presence in the land? Not necessary. […] Both have links to this land – nobody can claim exclusivity. When we start changing this question in the conflict from a question of who belongs and who does not belong, to a question of how do we both belong, eighty percent of the problems will be out of the table.” (51:05)

“For us now, with two million people under plastic tents in Gaza, if you go and ask them, “what is your national aspiration?”, they will tell you, “a bottle of water” – this is our national aspiration, now.” (56:30)

“By the end of the day, we are always one Israeli election away from peace.” (57:48)

“We have seen to what extent they went in Gaza and the world did not stop them. Do you need more proof? Why do I need to talk to the world? I need to talk to them! And they are only five minutes away.” (58:10)

“Only we the Palestinians can move the hearts of the Israelis.” (59:00)

Dialogue

“It was only Trump who was able to shut down the guns. And I think it is only Trump who will be able to push this plan from point one to point twenty. Is this the best we can have? Definitely no. Is this the only game in town? Apparently yes. What should we do as Palestinians? I think we should be engaged positively.” (01:18:30)

“We should not forget that we do have common humanity. […] We do have common humanity. And this common humanity will rescue both of us. But we need to revive it” (01:24:50)

“It’s tough. Our hearts are filled with hard feelings. We can understand it. But we need to understand that it’s on both sides. The only way if we want to be responsible to every kid that lost his life in Gaza – and trust me whenever I see a video coming of Gaza of a baby being killed before his birth certificate is printed, I cry. But if we want to be responsible, we need to get rid of revenge. We need to replace revenge by hope – and it’s happening!” (01:26:22)

“The damage is not only in the homes, the damage is also in the hearts. And we need to fix both. Reconstruction parallel with reconciliation is what we need now.” (01:37:08)

“I want to conclude by mentioning one story. There is a trend now among Israelis and Palestinians to put on this necklace with a full map. Now, you can differentiate the Israelis from the Palestinians because the Israelis they put the full map with the Golan heights. And by the way, both necklaces are product of the same factory in China – they just wrap it differently and sell it. Now, I look at people, I was in your university yesterday [Amal Jamal’s university: Tel Aviv University], and I saw some Palestinians and some Israelis with these map necklaces, but they are sitting in the same cafeteria, talking to each other. So, in reality they are coexisting, at least in the university. This necklace is part of the confusion. But we started to be confused to this level: Few months ago, I was invited to a conference in Israel as a speaker and there were two Jewish American ladies in the first row, I was on the panel, and they had the necklace. And then I asked them “ladies, where did you buy this necklace?”, they said “we bought it in the old city”, I told them “okay, this is the Palestinian ‘from the river to the sea’, it does not have the Golan heights”. We are so confused that we started putting the symbol of the other side and not noticing the difference. Trust me: Israelis and Palestinians are capable to co-exist. There is political confusion. Leaders have kidnapped us into bunkers of uncertainty and mistrust. And this could be treated.” (01:46:27)

“You might ask the Palestinians: Do you prefer the one-state or two-state solution? And they will tell you: Let the Israelis decide. […] Let them choose. What we will not accept as Palestinians is the current situation of the two-floor solution, where they are in the noble floor and we are in the servant floor. This cannot continue. […] Israelis need to decide now: Do they want annexation or do they want two-state solution. They need to decide now, they cannot continue postponing it. And we Palestinians we need to decide on something that is more painful, problematic, contradictory – but it’s a must. We need to choose between the two-state solution with an independent Palestinian state and a right of return, because we cannot have both. We cannot have our own state and ask millions of refugees to go to Israel. It doesn’t work. […] They need to choose, we need to choose – and I think it’s time to take this very hard decision. This is the only way. A compromise is giving up something that you deserve.” (01:48:52)

Questions

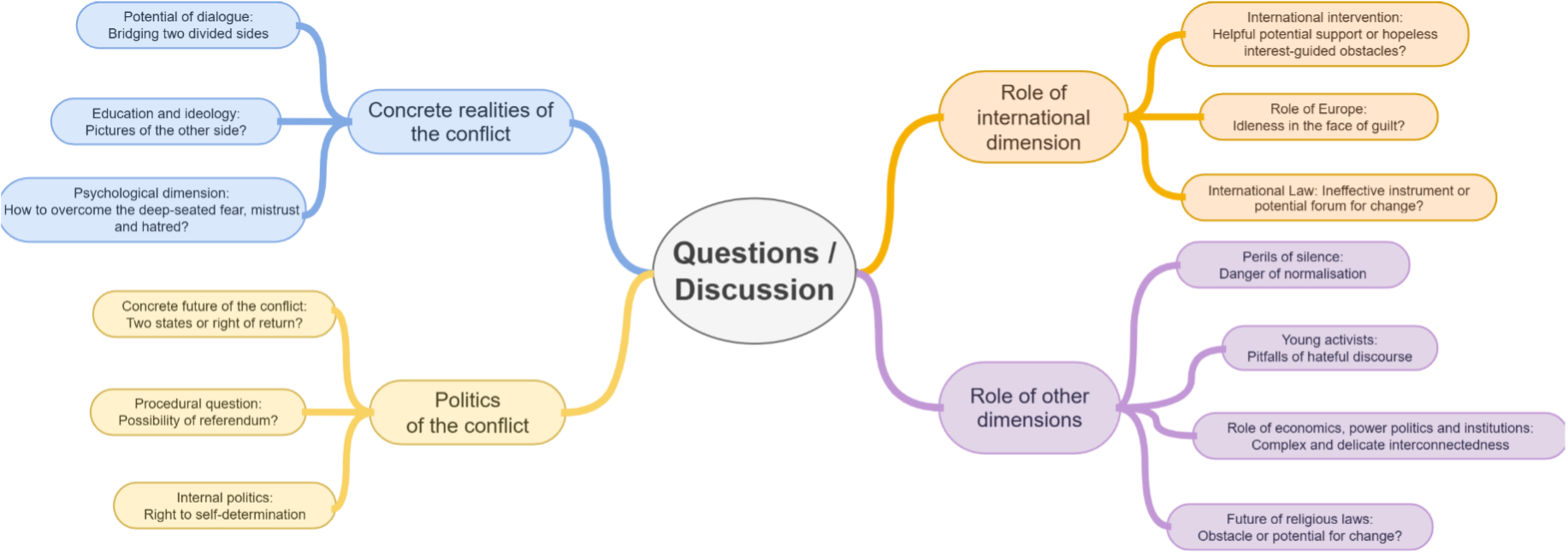

After the opening statements and the dialogue between the speakers, the audience had the opportunity to ask questions by writing them down on a piece of paper which were then collected and summarised. In the following graph, the main points raised in the questions of the audience shall be illustrated.